The term Japanese Gothic architecture might initially seem like a contradiction. When one typically thinks of Gothic grandeur, images of towering European cathedrals with their flying buttresses and stained-glass windows come to mind. Yet, the introduction and adaptation of Western architectural styles in Japan, particularly during the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) and subsequent periods, led to fascinating and often unique interpretations. This wasn’t a direct copy-paste; instead, it was a complex process of cultural exchange, technological transfer, and artistic synthesis, resulting in buildings that blended European forms with Japanese sensibilities, materials, and functional needs. Exploring this intriguing phenomenon reveals how Japanese Gothic style became a symbol of modernization, education, and national identity, leaving a distinctive, albeit often overlooked, mark on the nation’s architectural landscape.

The Arrival of Western Influence

Prior to the Meiji Restoration, Japanese architecture had centuries of its own rich traditions, characterized by timber construction, intricate joinery, and a harmonious relationship with nature, exemplified by temples, castles, and traditional houses. The sudden opening of Japan to the West brought a flood of new ideas, technologies, and architectural styles, including Gothic.

A. Isolation and Opening (Sakoku to Meiji Restoration):

* Edo Period Isolation (1603-1868): For over two centuries, Japan pursued a policy of strict national isolation, limiting contact with the outside world. This fostered the development of unique indigenous architectural styles largely untouched by Western influences.

* Meiji Restoration (1868): This pivotal period marked the end of the feudal samurai era and the rapid modernization and Westernization of Japan. The new Meiji government actively sought to adopt Western science, technology, and institutions to strengthen Japan and compete on the global stage.

* Western Advisors and Architects: To facilitate this modernization, the Japanese government invited numerous foreign advisors, engineers, and architects, primarily from Britain, France, Germany, and America. These individuals played a crucial role in introducing Western architectural styles and construction techniques.

* Desire for Modernity: The adoption of Western architecture, including Gothic elements, was a conscious effort to demonstrate Japan’s newfound modernity, sophistication, and alignment with the “civilized” nations of the West. It was a visual declaration of a break from the past.

B. The Introduction of Gothic Elements:

* Early Western Buildings (Late 19th Century): The first Western-style buildings in Japan were often constructed for foreign legations, trading houses, and educational institutions, initially built by foreign architects.

* Brick and Stone Construction: Unlike traditional Japanese timber structures, Western buildings often utilized brick, stone, and later, steel and concrete. This required importing new materials, tools, and construction knowledge.

* Influence on Public Buildings: Gothic influence began to appear in government buildings, universities, and churches, particularly those with a desire to project an image of authority, tradition (in the Western sense), or scholarly rigor.

* Eclecticism: Early Meiji-era architecture was often eclectic, blending various Western styles (Gothic, Renaissance, Neoclassical) rather than adhering to one strictly. Gothic elements were chosen for their perceived grandeur and solemnity.

C. The Role of Christian Missions:

* Church Architecture: While Christianity had a complex history in Japan (including periods of severe repression), the Meiji era saw a degree of religious freedom and the re-establishment of Christian missions.

* Gothic as Religious Symbolism: For many Christian denominations, Gothic architecture was deeply associated with traditional church design and spiritual reverence. As such, many churches built in Japan during this period adopted Gothic forms, ranging from simple chapels to more elaborate cathedrals.

* Foreign and Japanese Architects: Initially, foreign missionaries and architects designed these churches, but increasingly, Japanese architects educated in Western techniques began to contribute.

Key Characteristics and Adaptations in Japanese Context

When Gothic elements were incorporated into Japanese architecture, they rarely appeared in their pure European form. Instead, they were adapted, reinterpreted, and sometimes subtly blended with local sensibilities.

A. Material Adaptations:

* Brick as a Substitute for Stone: Japan lacked readily available quarry stone suitable for large-scale Gothic masonry. As a result, brick became the primary building material, often clad in plaster or stucco to mimic stone, or left exposed as a distinctive feature. The use of red brick became a symbol of modernization.

* Timber Frame Influence: Even when adopting brick or stone, the underlying structural principles of Japanese timber framing, with its emphasis on flexibility and earthquake resistance, sometimes subtly influenced the construction methods or the way loads were distributed.

* Early Reinforced Concrete: As the 20th century progressed, reinforced concrete became more common, allowing for greater structural freedom and the creation of larger, more open spaces, while still retaining Gothic-inspired forms.

B. Structural Reinterpretations:

* Less Emphasis on Flying Buttresses: Due to Japan’s seismic activity, the complex, slender structure of European flying buttresses was often considered less suitable or too challenging to construct. Japanese interpretations of Gothic forms might have thicker walls or rely on internal buttressing.

* Simpler Vaulting: While pointed arches were adopted, the elaborate ribbed vaults characteristic of European Gothic were often simplified or omitted, particularly in early adaptations. Flat ceilings or simpler vaulting solutions might be used instead, especially in public buildings.

* Focus on Facade and Ornamentation: The external appearance, particularly the façade, often received more attention in terms of Gothic detailing (pointed arches, rose window-like elements, decorative tracery) than the full structural system.

C. Scale and Proportion:

* Varied Scale: While some larger public buildings and cathedrals adopted monumental Gothic scale, many smaller institutions, schools, and churches incorporated Gothic elements on a more modest, often more manageable, scale.

* Blended Proportions: The extreme verticality of European Gothic was sometimes softened or subtly adjusted to fit within existing urban contexts or to blend with local aesthetic preferences, which favored a more grounded appearance.

D. Decorative Motifs and Blending:

* Gothic Motifs on Non-Gothic Structures: It was common to see Gothic Revival elements (pointed arch windows, pinnacles, spires, decorative tracery) applied to buildings that were otherwise structurally or functionally not strictly Gothic. This was a superficial adoption of the style.

* Hybrid Styles: Many buildings showcased a fascinating hybridity, combining Gothic elements with Renaissance Revival, Neoclassical, or even subtle Japanese decorative motifs. This eclectic approach was characteristic of the early Westernization period.

* Stained Glass Adaptation: While stained glass was used, the specific narratives and artistic styles might be adapted to local contexts or the specific religious denominations commissioning the work. Japanese artisans might contribute to its creation.

Notable Examples and Typologies in Japan

While not as numerous or consistently pure as their European counterparts, several significant buildings in Japan exemplify the various interpretations and applications of Gothic architecture.

A. Educational Institutions:

* Keio University (Mita Campus, Tokyo): Founded by Yukichi Fukuzawa, Keio Gijuku (its earlier name) adopted a prominent Gothic Revival style for many of its early brick buildings, notably the Old University Library (1912). This was intended to symbolize academic rigor and a connection to Western intellectual traditions.

* Doshisha University (Kyoto): Another prominent university with a Christian foundation, Doshisha features several brick Gothic-style buildings, such as the Clark Memorial Hall (1894), reflecting the influence of American missionary architects.

* St. Paul’s University (Rikkyo University, Tokyo): Similar to Doshisha, as a Christian-affiliated institution, Rikkyo University boasts several distinctive Gothic Revival brick buildings that convey a sense of gravitas and history.

* Significance: For these institutions, Gothic architecture was a deliberate choice to align themselves with prestigious Western universities and to project an image of serious, academic learning.

B. Churches and Cathedrals:

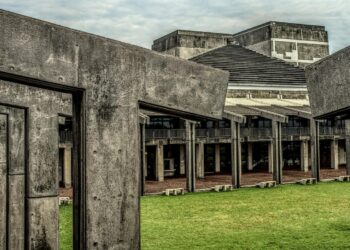

* St. Mary’s Cathedral (Tokyo): While the original church was destroyed in WWII, its successor (designed by Kenzo Tange, completed 1964) is a masterpiece of modern architecture that uses concrete in a bold, almost Brutalist, but highly sculptural way, sometimes seen as a contemporary interpretation of the Gothic pursuit of light and spiritual ascent, albeit without explicit Gothic forms.

* Smaller Local Churches: Numerous smaller Christian churches built across Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries adopted simpler Gothic Revival elements, such as pointed arched windows, small spires, and sometimes brick construction. These were often more modest adaptations.

* Oura Church (Nagasaki): While not strictly Gothic, this significant Catholic church (built 1864) does incorporate some Western ecclesiastical design elements, showing early European influence.

* Significance: These churches provided places of worship for growing Christian communities and visually represented the presence of Western religion in Japan.

C. Public and Commercial Buildings:

* Former Tokyo Imperial University Library (Tokyo, 1928): While primarily Neo-Renaissance, it exhibits some Gothic details in its fenestration and ornamentation, indicative of the eclectic approach of the era.

* Early Government Buildings: Some early prefectural offices or civic buildings might feature Gothic-inspired details, intended to convey solemnity and a modern, Westernized governmental presence.

* Bank of Japan (Tokyo, 1896, designed by Kingo Tatsuno): Though predominantly Renaissance Revival, elements of its ornate stone and brickwork show the detailed craftsmanship common in the period of Western architectural adoption. While not Gothic, it’s representative of the new materials and techniques.

* Significance: For these secular buildings, Gothic elements often served to convey a sense of enduring authority, stability, and a modern, international aesthetic for institutions of the new Japan.

Challenges and Interpretations

The adoption of Gothic architecture in Japan faced unique challenges, leading to distinctive interpretations that reflected both practical constraints and a cultural filtering process.

A. Seismic Considerations:

* Earthquake Resistance: Japan is highly seismic. Traditional Japanese timber architecture was inherently flexible and earthquake-resistant due to its joinery and light materials. Massive, rigid stone or brick structures of European Gothic posed significant challenges.

* Adaptations: Japanese architects and engineers had to develop new techniques or reinforce Western structures to withstand earthquakes, sometimes leading to less intricate forms or more robust construction than their European counterparts. Reinforced concrete, which was introduced later, provided better seismic resistance.

B. Material Availability and Craftsmanship:

* Lack of Suitable Stone: As mentioned, the scarcity of large, workable stone quarries in many parts of Japan meant that brick became the dominant material for Western-style buildings, often requiring imported knowledge for its production and laying.

* Artisan Training: Japanese carpenters were masters of wood, but skills in Western stone masonry and bricklaying had to be imported and taught, leading to a period of learning and adaptation for local artisans.

* Climate Adaptation: The humid Japanese climate often required adaptations to building materials and ventilation strategies, different from the drier climates of much of Europe where Gothic thrived.

C. Cultural Integration and Aesthetic Filtering:

* Symbolic vs. Functional Adoption: Often, Gothic elements were adopted more for their symbolic value (modernity, Western prestige, religious association) than for their underlying structural principles (e.g., using pointed arches as decorative elements rather than for vaulting).

* Blending with Local Context: While Gothic elements were prominent, architects often subtly integrated them into designs that still responded to Japanese urban planning principles or aesthetic preferences. For example, some buildings might have a more grounded appearance or incorporate Japanese garden elements.

* Westernization vs. Japanization: The period saw a tension between fully adopting Western styles and adapting them to create a uniquely Japanese modern architecture. Gothic architecture often fell into the latter category, becoming a “Japanized” version.

* Perceived “Heaviness”: For many Japanese, the inherent massiveness and dark interiors of some Gothic structures contrasted with traditional Japanese aesthetics of lightness, natural light, and open spaces.

D. The Shift Beyond Gothic:

* Emergence of Modernism: By the early 20th century, particularly after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 (which highlighted the vulnerability of brick structures), modern architectural movements (Art Deco, International Style, Bauhaus) gained traction. These styles, with their emphasis on steel, concrete, and simpler forms, often replaced the more ornate historical revival styles like Gothic.

* National Identity and Indigenous Styles: A growing emphasis on developing a distinct Japanese modern architecture, often drawing from traditional Japanese forms and materials, meant that pure Western revival styles became less prominent.

A Unique Architectural Chapter

While not as globally recognized as European Gothic, the Japanese interpretations of the style represent a unique and valuable chapter in the nation’s architectural history.

A. Preservation Challenges:

* Earthquake Damage and Fire: Many early Western-style buildings, including Gothic-influenced ones, were destroyed or severely damaged by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the firebombings of World War II.

* Modern Development: Rapid urban development in post-war Japan often led to the demolition of older buildings, including those from the Meiji and Taisho eras, to make way for new structures.

* Maintenance: Older brick and early concrete structures require ongoing maintenance to withstand the elements and seismic activity.

B. Reappraisal and Appreciation:

* Historical Significance: Surviving examples of Japanese Gothic architecture are increasingly valued for their historical significance, representing a crucial period of Westernization and architectural experimentation.

* Unique Synthesis: Architects and historians now appreciate the unique synthesis of Eastern and Western elements found in these buildings, recognizing them as distinct cultural artifacts.

* Tourism and Heritage: Some well-preserved examples attract tourists interested in Japan’s modern history and architectural heritage. Efforts are being made to register and protect these buildings.

C. Influence on Contemporary Design:

* Material Exploration: The early use of brick and concrete in these buildings paved the way for modern construction techniques in Japan.

* Cultural Dialogue: The historical dialogue between Western forms and Japanese sensibilities continues to influence contemporary Japanese architecture, often leading to designs that are globally modern yet distinctly Japanese.

* Lesson in Adaptation: The Japanese experience with Gothic architecture serves as a valuable case study in how imported architectural styles are not merely copied but transformed through local constraints, cultural preferences, and technological capabilities.

Conclusion

The fascinating story of Japanese Gothic architecture is not one of direct imitation, but of ingenious adaptation and cultural synthesis. Born from Japan’s earnest desire for modernization and a rapid embrace of Western knowledge during the Meiji Restoration, it brought soaring forms, pointed arches, and the robust solidity of brick into a landscape traditionally defined by wood and lightness. While often distinct from its European progenitors—modified for seismic resilience, constrained by materials, and filtered through Japanese aesthetics—these buildings stand as powerful symbols of a nation in transition. They represent a unique and often beautiful blend of traditions, demonstrating how architectural styles can transcend their origins to take on new meanings and forms in distant lands. The legacy of East meets West in these structures continues to offer a compelling narrative of innovation, identity, and the enduring power of architectural expression.