The art of the Japanese garden, a timeless tradition steeped in philosophy, history, and meticulous craftsmanship, is more than just landscaping. It is a profound practice of creating sanctuaries of peace and contemplation, using natural elements to evoke a sense of harmony, tranquility, and connection to the natural world. Far from a random collection of rocks and plants, these gardens are carefully sculpted microcosms of nature, revealing profound design secrets that have been refined over centuries. Understanding the core principles, the diverse styles, and the philosophical underpinnings of Japanese garden design is crucial for landscape architects, gardeners, and anyone seeking to cultivate a deeper sense of serenity and beauty in their own outdoor spaces.

A Philosophical Foundation

At the heart of every Japanese garden lies a deeply philosophical approach to nature and human existence. The design is not just for visual appeal; it is intended to be a spiritual experience, a place for meditation, and a reflection of a specific worldview. This philosophical core is what truly distinguishes it from other garden traditions.

A. Core Philosophical Principles

Several key concepts form the spiritual and aesthetic bedrock of Japanese garden design.

- Shakkei (Borrowed Scenery): This principle involves intentionally incorporating elements from outside the garden, such as a distant mountain, a neighbor’s tree, or a far-off building, into the composition. The garden is designed to act as a frame, borrowing a larger, external landscape to create a sense of expansive space and deep connection to the surroundings.

- Wabi-Sabi (Beauty in Imperfection): Wabi-sabi is the aesthetic ideal that finds beauty in what is imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. In gardens, this is reflected in the use of aged materials like moss-covered stones, weathered wood, and asymmetrical arrangements. It celebrates the natural cycles of growth and decay, a reminder of the transient nature of life.

- Ma (Negative Space): Ma refers to the intentional use of empty space to create a sense of pause and contemplation. The emptiness is as important as the filled spaces. It allows the mind to rest and the other elements of the garden to stand out, creating a dynamic balance between presence and absence.

- Yin and Yang: Derived from Taoist philosophy, this principle is about creating a dynamic balance of opposites. In gardens, this is seen in the contrast between hard and soft elements (rocks and moss), still and moving water, vertical and horizontal lines, and light and shadow. The harmony of these opposites creates a sense of natural equilibrium.

- Symbolism and Metaphor: Every element in a Japanese garden is carefully chosen and often holds a deeper symbolic meaning. Rocks can represent mountains, ponds can represent oceans, and sand can represent water. This creates a miniature, metaphorical landscape that invites reflection and imaginative interpretation.

- Austerity and Restraint: Japanese gardens, particularly Zen gardens, are characterized by a profound sense of restraint and minimalism. The focus is on a few carefully chosen elements, arranged to convey a powerful message without clutter or excess. It is a practice of “less is more.”

B. The Connection to Nature

The goal of a Japanese garden is to bring the essence of nature into a controlled, human-made space. It is a deep respect for the wild, untamed world, captured and refined. The garden is a microcosm of the universe, a place where a single rock can represent a mountain and a small raked sand pattern can represent the vastness of the ocean.

The Elements of Design

To create these philosophical landscapes, Japanese garden design relies on a specific set of core elements and a meticulous approach to their arrangement. The master gardener understands how to combine these elements to evoke the desired emotion and aesthetic.

A. Water

Water, in its various forms, is a central and dynamic element in most Japanese gardens, symbolizing purity, life, and the flow of time.

- Ponds and Lakes: Represent the ocean, a source of life and tranquility. Their still surface reflects the sky and surrounding foliage, creating a sense of depth and expansiveness.

- Streams and Waterfalls: Symbolize the journey of life, from a powerful, dynamic source (waterfall) to a gentle, meandering path (stream). The sound of moving water is also a key sensory component, contributing to the garden’s tranquil atmosphere.

- Tsukubai (Water Basin): A small stone basin, typically with a bamboo water spout (kakehi), used for ritual purification. It’s often found near tea houses and provides a focal point for quiet contemplation and a reminder of humility.

- Dry Waterfalls (Karesansui): In Zen gardens, waterfalls are often represented metaphorically by vertically placed rocks and white sand, symbolizing the powerful force of water without its physical presence. This encourages abstract, imaginative contemplation.

B. Stone

Stones are the enduring, structural elements of the garden, representing mountains, islands, and the fundamental strength of nature.

- Arrangement (Sanzon Ishi): Stones are almost never placed in isolation. They are arranged in groups, often in odd numbers, to create a natural, asymmetrical composition. A common arrangement is the Sanzon Ishi, a three-stone grouping that represents the Buddhist trinity.

- Variety and Placement: The size, shape, and texture of each stone are carefully considered. They are placed with purpose, often partially buried to look like a natural outcropping, connecting them to the earth and giving them a sense of permanence.

- Stepping Stones (Tobi-ishi): These are not just for walking; they are placed to guide visitors through the garden, controlling the pace and the view. They force a person to look down and be mindful of their steps, creating a slower, more deliberate experience.

C. Plants

Plants are used with restraint and purpose to provide texture, color, and a sense of seasonal change.

- Evergreens: Pines, junipers, and other evergreens are staples, symbolizing longevity and endurance. They provide a stable, unchanging backdrop throughout the year.

- Deciduous Trees: Maples (Momiji) and cherry trees (Sakura) are planted for their dramatic seasonal changes. The brilliant reds of autumn and the fleeting beauty of spring blossoms are reminders of the cycle of life and the principle of impermanence (Wabi-sabi).

- Moss: Moss is a crucial element, symbolizing age, tranquility, and the passage of time. It is used to cover the ground and stones, creating a soft, green carpet that unifies the composition.

- Flowering Plants (with restraint): Unlike Western gardens, Japanese gardens use flowering plants sparingly, often in small, contained areas, to provide subtle accents rather than overwhelming the senses.

- Pruning (O-gari): The meticulous art of pruning is used to sculpt plants, not just to maintain them, but to make them look like ancient, weathered trees or natural landscapes.

D. Sand and Gravel

In a Karesansui (dry landscape) garden, sand and gravel are the most important elements, representing water and creating a space for quiet meditation.

- Raking Patterns: The sand is carefully raked in patterns that symbolize flowing water, waves, or ripples. The act of raking itself is a form of meditation for the gardener.

- Symbolism: The white sand represents the ocean, and the rocks placed within it represent islands or mountains, creating an abstract, symbolic landscape.

- Focus on Stillness: The absence of real water forces the mind to find a different kind of tranquility, one born of stillness, austerity, and imaginative contemplation.

Diverse Styles of Japanese Gardens

The principles of Japanese garden design have given rise to several distinct styles, each with its own history, purpose, and aesthetic.

A. Karesansui (Dry Landscape) Garden

- Purpose: Primarily for meditation and philosophical contemplation.

- Key Elements: Raked white sand or gravel, a few carefully placed rocks, and sometimes moss.

- Aesthetic: Minimalist, abstract, and austere. The goal is to evoke the essence of nature with the fewest possible elements.

- History: Developed in the Zen Buddhist monasteries during the Muromachi period. The most famous example is the Ryoan-ji Temple garden in Kyoto.

B. Tsukiyama (Hill and Pond) Garden

- Purpose: For walking and enjoying the view from various vantage points.

- Key Elements: Artificial hills (Tsukiyama), a central pond, streams, bridges, lanterns, and a variety of plants. It is a miniature representation of a natural landscape with mountains, lakes, and forests.

- Aesthetic: More naturalistic and expansive than a Karesansui garden. It’s meant to be a journey of discovery.

- History: Developed for the elite during the Heian and Edo periods. Examples include the Kenroku-en in Kanazawa and the Rikugi-en in Tokyo.

C. Chaniwa (Tea Garden)

- Purpose: To prepare the mind for the Japanese tea ceremony.

- Key Elements: A simple, rustic aesthetic (Sukiya style) with a stepping stone path (Roji) leading to a tea house. It features a Tsukubai (water basin), lanterns, and minimal, naturalistic planting.

- Aesthetic: Austere, rustic, and peaceful. The path to the tea house is intentionally designed to be a meditative journey, cleansing the mind of worldly thoughts before the ceremony.

- History: Developed in the Azuchi-Momoyama and Edo periods, reflecting the quiet, spiritual nature of the tea ceremony.

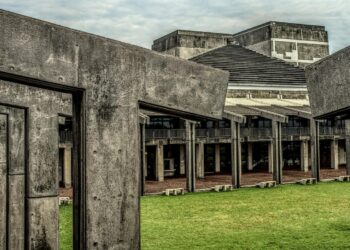

D. Tsubo-niwa (Courtyard Garden)

- Purpose: To bring nature and light into a small, enclosed space, typically within an urban home or building.

- Key Elements: Limited space, often enclosed by walls, with a few key elements like a small stone, bamboo, and moss.

- Aesthetic: Minimalist and intimate. The goal is to create a small, private sanctuary within a confined space.

- History: Historically found in the townhouses (Machiya) of Kyoto. Today, the principles are widely used in urban design and small residential gardens.

A Guide to Creating Your Own Japanese Garden

While creating an authentic masterpiece takes a lifetime of study, the core principles can be applied to any space, big or small, to evoke a sense of tranquility and order.

A. Planning and Conceptualization

- Choose a Style: Decide on the style that best suits your space and your purpose. A small urban space might be perfect for a Tsubo-niwa, while a larger backyard could accommodate a simplified Tsukiyama.

- Embrace Asymmetry: Avoid perfect symmetry. Instead, use odd numbers and unbalanced arrangements to create a more natural, organic feel.

- Prioritize Ma (Negative Space): Resist the urge to fill every corner. The empty space is what allows the key elements to breathe and be appreciated.

- Create a Journey: Even in a small space, use stepping stones or a path to guide the eye and control the view, creating a journey of discovery rather than a single static view.

- Respect Symbolism: Understand the symbolism of the elements you choose. For instance, a single large stone can be a metaphor for a mountain, creating a sense of scale in a small space.

B. Selecting and Arranging Elements

- Rocks: The most important non-living element. Choose a few well-placed rocks with interesting shapes and textures. Place them partially buried to create a sense of permanence and connection to the earth.

- Water: If a real pond is not possible, a dry rock garden with raked sand can beautifully represent water. A small bamboo fountain (Shishi-odoshi) can also provide the tranquil sound of water without a large pond.

- Plants: Use plants with restraint. Start with a few evergreens for a stable base and add one or two deciduous trees for seasonal interest. Moss is a fantastic ground cover that unifies the design. Prune plants to give them a natural, windswept look.

- Paths: Use stepping stones (Tobi-ishi) to control the pace of movement and create a sense of anticipation. Avoid a straight, direct path, which rushes the journey.

- Lanterns and Bridges: These are key human elements. Place a stone lantern (Toro) at a key focal point, not just as a light source, but as a symbolic gesture of enlightenment. A small bridge can be a powerful metaphor for a journey or a transition.

Conclusion

The Japanese garden is a timeless legacy of beauty and serenity, offering a profound lesson in the art of living harmoniously with nature. Its design secrets are not just a set of rules, but a philosophical framework that teaches us to find beauty in imperfection, power in stillness, and connection in simplicity. By understanding the principles of Shakkei, Wabi-sabi, and Ma, and by thoughtfully incorporating elements like stone, water, and plants, we can all become creators of these tranquil sanctuaries.

In a world of increasing noise and distraction, the Japanese garden provides a vital oasis, a place for contemplation and spiritual renewal. It’s a reminder that true beauty often lies in restraint and that the most profound designs are those that honor the natural world. Whether as a full-scale landscape or a small, symbolic corner, the principles of Japanese garden design offer a powerful toolkit for cultivating peace and a deeper connection to the world around us.