The phrase Japanese Brutalist architecture immediately conjures images that seem at odds: the raw, monumental concrete of Brutalism clashing with the refined, often ephemeral qualities of traditional Japanese design. Yet, during the post-World War II era, particularly from the 1950s through the 1970s, Japan embraced and profoundly reinterpreted Brutalism, forging a distinctive style that merged its core principles with unique local sensibilities, technological advancements, and a deep philosophical undercurrent. Far from being mere imitation, this movement, often associated with the Metabolist architects, created structures that were bold, sculptural, and deeply expressive of their materials, leaving a powerful and often surprising mark on the nation’s urban and natural landscapes. Exploring Brutal Grace: Japanese Concrete Forms reveals a fascinating chapter where Eastern precision met Western might, resulting in an architectural legacy that is both globally significant and uniquely Japanese.

The Post-War Crucible

Japan’s post-war context provided fertile ground for the emergence of new architectural ideas. The devastation of war, coupled with a booming economy and a desire for rapid modernization, created a unique environment where architects could experiment with new materials and forms.

A. Post-War Reconstruction and Urbanization:

* Devastation and Renewal: Japanese cities, especially Tokyo, faced widespread destruction after World War II. This necessitated massive reconstruction efforts, providing architects with blank slates and opportunities to experiment with new urban planning concepts and building materials.

* Economic Boom: The rapid economic growth during the “economic miracle” era (1950s-1970s) provided the resources and demand for large-scale infrastructure, public buildings, and commercial complexes.

* Rapid Urbanization: As people flocked to cities for work, there was an urgent need for efficient, high-density housing and public amenities, prompting architects to explore new building typologies.

B. Encounter with European Modernism:

* Le Corbusier’s Influence: While the term “Brutalism” originated in Europe (from béton brut or “raw concrete,” popularized by Le Corbusier), his influence in Japan was profound. His work, particularly the Unité d’habitation and his philosophical approach to concrete, resonated deeply with Japanese architects.

* International Exposure: Japanese architects who had studied abroad or engaged with international architectural discourse brought back ideas from European modernism, including Brutalism’s emphasis on material honesty and structural expression.

* Formal Adoption: Unlike eclectic Western revival styles (like Japanese Gothic), Brutalism’s directness and emphasis on raw material suited the pragmatic and efficient spirit of post-war reconstruction.

C. The Metabolist Movement (1960s): A Japanese Philosophical Layer:

* Key Figures: Kenzo Tange, Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and Fumihiko Maki were central figures in the Metabolist movement, which was revealed at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo.

* Biological Analogy: Metabolism proposed that buildings and cities should be designed like living organisms, capable of growth, change, and regeneration. This was a radical departure from fixed, static structures.

* Modular and Adaptable Design: Metabolist ideas, often expressed through Brutalist concrete forms, emphasized modular components that could be added or removed over time. This included “plug-in” capsules, interchangeable units, and flexible frameworks.

* Urban Scale: Metabolism often tackled urban-scale problems, proposing vast, megastructural solutions for cities that could evolve with their populations.

* Impact on Brutalism: Metabolism provided a unique philosophical and theoretical framework for the robust, adaptable, and sometimes futuristic expressions of Brutalism in Japan. It transformed Brutalism from a mere aesthetic into a dynamic system for urban living.

The Essence of Japanese Brutalism

Japanese Brutalism, while sharing core tenets with its Western counterpart, developed its own unique set of characteristics, influenced by local context, aesthetics, and innovative thinking.

A. Mastery of Concrete:

* Beton Brut with Precision: While celebrating “raw concrete,” Japanese Brutalist architects often applied a meticulous level of craftsmanship. The wooden formwork used to cast the concrete left incredibly precise and textured patterns (taguchi-mokume), elevating raw concrete to a refined art form. The attention to detail in the pouring and finishing often surpassed that seen in some Western examples.

* Exposed Aggregates: Sometimes, the concrete surface was bush-hammered or sandblasted to expose the aggregates within, creating a rugged yet controlled texture.

* Contrast with Traditional Materials: The raw concrete was often juxtaposed with traditional Japanese materials like wood, tatami mats, or gardens, creating a dialogue between old and new, roughness and refinement.

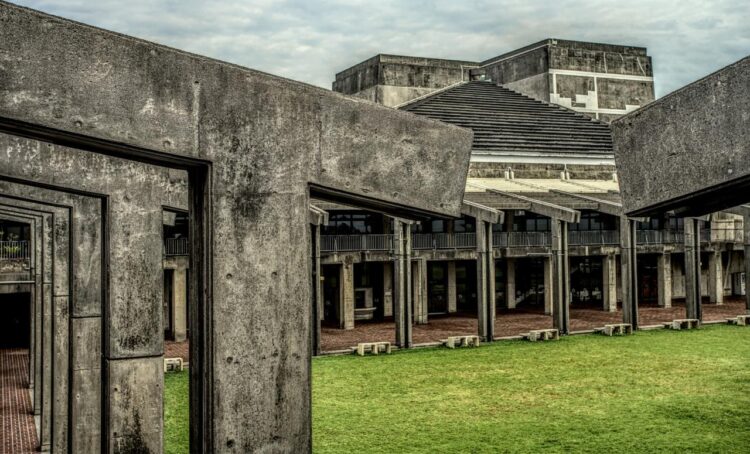

B. Sculptural and Monumental Forms:

* Dynamic Shapes: Japanese Brutalism often featured highly sculptural and geometric forms, creating dramatic silhouettes and impactful masses. Buildings were conceived as singular, powerful objects rather than simple boxes.

* Heavy Volumes: An emphasis on the sheer weight and volume of concrete, creating a sense of permanence and imposing presence. This was particularly evident in public and institutional buildings.

* Interconnected Masses: Designs frequently involved interlocking volumes, tiered platforms, and elevated walkways, creating complex spatial relationships both inside and out.

C. Integration of Light and Shadow:

* Dramatic Play: Architects masterfully used the properties of concrete to create deep recesses, overhangs, and textured surfaces that interacted dramatically with natural light, producing striking patterns of light and shadow throughout the day.

* Skylights and Atriums: Despite the solid exterior, many Japanese Brutalist buildings incorporated large skylights, internal courtyards, and vast atriums to bring abundant natural light into the interior spaces, contrasting with the more enclosed feel of some Western Brutalist structures.

* Zen Influence: The appreciation for light and shadow, and the way they define space, can be seen as an echo of traditional Japanese aesthetics, particularly those found in Zen gardens and architecture.

D. Emphasis on Circulation and Public Space:

* Elevated Platforms and Piloti: Buildings were often lifted on massive pilotis (columns) or integrated with elevated plazas and walkways, creating public spaces beneath and around the structures. This was partly a response to limited ground space in dense urban environments and earthquake considerations.

* Grand Staircases and Ramps: Prominent, often sculptural, staircases and ramps were common, guiding visitors through the monumental spaces and emphasizing movement and procession.

* Engagement with Urban Context: Many Brutalist projects aimed to integrate with the surrounding city, not just sit in isolation. They sought to create new public spaces and pathways within the urban fabric.

E. Symbolism and Expression:

* Strength and Resilience: The robust, unyielding nature of concrete symbolized Japan’s post-war resilience, its determination to rebuild, and its aspirations for a strong future.

* Technological Prowess: The complex forms achievable with concrete showcased Japan’s growing technological capabilities and its embrace of modern construction methods.

* Philosophical Depth: For Metabolist architects, the brutalist forms expressed ideas of organic growth, adaptability, and the relationship between humanity and mega-structures.

Iconic Architects and Their Masterworks

Japanese Brutalism is inextricably linked with the visionary architects who pushed its boundaries, creating buildings that remain seminal works of 20th-century architecture.

A. Kenzo Tange (1913-2005): The Master Innovator:

* Yoyogi National Gymnasium (1964): While technically not Brutalist in its external material (it uses steel cables and roof), its monumental concrete base, sculptural form, and daring structural expression profoundly influenced the Brutalist movement in Japan. Its use of suspended roof structure was revolutionary.

* Kagawa Prefectural Government Office (1958): Often cited as an early masterpiece of Japanese Brutalism. Its exposed concrete, modular facade, and pilotis echoed Le Corbusier but with a distinct Japanese sensitivity to scale and structure. It aimed for transparency between government and public.

* Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (1955): A powerful early work using concrete, with a strong emphasis on light and shadow, creating a solemn and reflective space.

* St. Mary’s Cathedral (Tokyo, 1964): A bold, highly sculptural concrete structure with an awe-inspiring interior, creating a powerful spiritual space without overt traditional Gothic forms, but embodying the Gothic pursuit of light and spiritual ascent through modern means.

* Influence: Tange’s work was central to establishing Japan’s architectural presence on the global stage and deeply influenced subsequent generations of Japanese architects.

B. Kiyonori Kikutake (1928-2011): Metabolist Pioneer:

* Sky House (1958): Kikutake’s own residence, a remarkable early Metabolist work that featured a large, single-volume concrete box raised on pilotis, with a flexible interior and “plug-in” furniture, demonstrating adaptability.

* Marine City (1958, Proposal): A visionary Metabolist project proposing a floating city made of modular concrete structures that could adapt to population growth and sea level changes.

* Shimane Prefectural Museum (1960): A more grounded example of his work, featuring bold concrete forms and a strong sense of weight.

C. Kisho Kurokawa (1934-2007): The Capsule Architect:

* Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972, Tokyo): The most iconic Metabolist building, featuring modular, detachable “capsules” plugged into a central concrete core. Each capsule was a tiny living or office unit, designed for flexibility and future replacement, embodying the Metabolist ideal of organic growth and change. It’s a prime example of Brutalism’s modular expression.

* The National Art Center, Tokyo (2007): While much later and not strictly Brutalist, Kurokawa’s later work continued to explore modularity and bold forms, showing a lineage from his Metabolist roots.

D. Fumihiko Maki (b. 1928): Collective Form and Refinement:

* Hillside Terrace Complex (1969-1992, Tokyo): A series of interconnected buildings that, while not purely Brutalist, showcase a sensitive approach to concrete and “collective form,” demonstrating how individual elements can form a larger, cohesive urban whole. It exhibits a refined sense of detail and urban integration.

* Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium (1990): While later, this project still uses bold, expressive forms and materials, reflecting a lineage of monumental public architecture.

E. Other Notable Contributions:

* Kunio Maekawa (1905-1986): A key figure in bringing modernism to Japan and an early advocate for exposed concrete, known for works like the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan (Tokyo Festival Hall, 1961), which exhibits strong, textured concrete forms and a monumental presence.

* Yoshinobu Ashihara (1918-2003): Known for his sophisticated use of materials and light, often using concrete with great elegance, as seen in the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (1975).

The Complex Legacy

Like Brutalism worldwide, Japanese Brutalism elicits strong reactions, from fervent admiration to outright disdain. Its legacy is a subject of ongoing debate and reappraisal.

A. Criticisms and Decline:

* Perceived Coldness and Ugliness: For many, the unadorned concrete and massive scale were seen as cold, alienating, and visually unappealing, especially in contrast to traditional Japanese aesthetics.

* Lack of “Human Scale”: Some critics argue that the monumental scale of many Brutalist buildings overwhelmed the individual, creating oppressive or daunting public spaces.

* Maintenance Issues: Exposed concrete, if not properly cared for, can stain, spall, and show signs of degradation over time, leading to a dilapidated appearance that fuels negative perceptions. This was a particular challenge in humid climates like Japan.

* Social Disconnect: Some large housing projects, while intended to be democratic, faced criticisms for fostering social isolation or failing to integrate well into existing communities.

* Energy Efficiency: Older Brutalist buildings were often not designed with modern insulation standards, leading to challenges in heating and cooling.

* Earthquake Damage (Early Designs): While a concern, the robust nature of the concrete actually performed well in many earthquakes, but initial fears and the impact of the 1923 Kanto Earthquake on earlier brick structures might have influenced public perception towards “heavy” buildings.

B. Arguments for Reappraisal and Appreciation:

* Sculptural Power: Proponents highlight the powerful, sculptural qualities of these buildings, which are often conceived as works of art in themselves, interacting dramatically with light and shadow.

* Honesty of Materials: The commitment to expressing concrete in its raw, unadorned state is seen as an ethical and aesthetic triumph, rejecting superficiality.

* Technological Innovation: These buildings pushed the boundaries of concrete construction, showcasing advanced engineering and craftsmanship.

* Symbolic Resonance: They represent a pivotal moment in Japan’s post-war identity—a period of resilience, modernity, and bold ambition.

* Urban Contribution: Many Brutalist projects, particularly those influenced by Metabolism, attempted to solve complex urban challenges by integrating public spaces, pathways, and flexible components into dense cityscapes.

* Reversibility of Deterioration: Modern cleaning and repair techniques can restore weathered concrete surfaces, revealing their original beauty.

* Instagrammable Aesthetics: A new generation, particularly through social media, has rediscovered the graphic and photogenic qualities of Brutalist forms, leading to a surge in appreciation.

C. Preservation and Adaptive Reuse:

* Demolition Threats: Many significant Brutalist buildings in Japan, like the Nakagin Capsule Tower (demolished in 2022), face demolition threats due to aging infrastructure, high maintenance costs, and changing urban development priorities.

* Conservation Efforts: Growing movements, both locally and internationally, advocate for the preservation of these buildings, recognizing their architectural and historical significance.

* Adaptive Reuse Potential: The robust, open floor plans and strong structures of many Brutalist buildings make them suitable for adaptive reuse, transforming them into new functions (e.g., museums, apartments, offices) while preserving their original character.

The Future of Japanese Brutalism

The influence of Japanese Brutalism extends beyond the specific buildings of the mid-20th century, subtly shaping contemporary architectural thought and practice.

A. Continued Influence on Contemporary Japanese Architects:

* Material Honesty: A deep respect for materials and their inherent qualities, evident in Brutalism, continues to be a hallmark of much contemporary Japanese architecture, even when using different materials.

* Refined Concrete Usage: While overt Brutalism is rare, the mastery of concrete pouring and finishing, honed during the Brutalist era, persists. Architects like Tadao Ando, while not a Brutalist, exemplifies the precise and poetic use of exposed concrete, showing a lineage.

* Integration with Nature: The Brutalist period, particularly Tange’s work, often explored the relationship between massive structures and natural elements. This dialogue continues in modern Japanese architecture’s quest for harmony.

* Emphasis on Structure and Form: The legacy of bold, sculptural forms and clear structural expression remains a strong current in Japanese architectural design.

B. Relevance of Metabolist Ideas:

* Urban Resilience: The Metabolists’ ideas about adaptable, expandable, and regenerative cities are increasingly relevant in the face of rapid urbanization, climate change, and demographic shifts.

* Modular Construction: The concept of modular “plug-in” architecture, though often too complex or costly for mass adoption, continues to be explored in experimental and high-tech housing solutions.

* Sustainable Cities: The Metabolist vision for integrating infrastructure and nature, and building for long-term evolution, offers valuable lessons for creating more sustainable and livable urban environments.

C. Global Reappraisal of Brutalism:

* Academic Study: Japanese Brutalism is gaining more attention in global architectural history and theory, recognized for its unique contributions to the movement.

* Popular Interest: A growing number of architectural tourists, photographers, and enthusiasts are actively seeking out and documenting these structures, driven by their distinctive aesthetics and historical narratives.

* New Conservation Models: The challenges of preserving these buildings in Japan are contributing to new approaches and strategies for conserving mid-20th-century modern architecture worldwide.

D. Technological Advancements in Concrete:

* Self-Healing Concrete: Research into concrete that can self-repair cracks could address some of the long-term maintenance issues associated with exposed concrete.

* Low-Carbon Concrete: Developments in “green concrete” technologies aim to reduce the environmental footprint of cement production, making concrete a more sustainable material for future construction.

* 3D Printing Concrete: Emerging technologies for 3D printing large-scale concrete structures could enable new forms and efficiencies, revisiting the material’s sculptural potential.

Conclusion

Japanese Brutalist architecture stands as a compelling and often poetic counterpoint to its Western origins. It is a powerful testament to Japan’s post-war spirit of renewal, its embrace of modern technology, and its profound ability to absorb and transform external influences into something uniquely its own. From Kenzo Tange’s monumental civic structures to Kisho Kurokawa’s futuristic capsule towers, these buildings, born from the raw honesty of concrete and the philosophical ambition of Metabolism, make a bold statement in the urban fabric. While facing ongoing challenges of perception and preservation, the brutal grace of these Japanese concrete forms is increasingly recognized for its innovative spirit, its masterful craftsmanship, and its enduring contribution to both global modernism and the distinct narrative of Japanese architecture. They serve as a powerful reminder that true architectural significance lies not just in aesthetic appeal, but in the ideas they embody and the future they dared to envision.